RUSSIA TO THE RESCUE

The term „humanitarian aid“ appeared only in the twentieth century. However, Russian builders, doctors, and engineers used to go on long expeditions much earlier than that to share their knowledge and experience with other Nations.

Legends of Ancient Times

The story starts when the Church in Russia was still above the State, as its role was much greater than the Grand duke or even the Tsar’s crown in uniting principalities, which were not so long ago divided from one another.

Many people know that the Russian army helped the Bulgarian people to win back their freedom and independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1879. But the peaceful campaigns in support of other Slavic brotherly nations in their most difficult times were no less important for the salvation of the Balkan peoples.

First of all, the collaboration concerned the preservation of national sacred sites. In the XV century, almost all the Orthodox nations had fallen into political dependence from Turkey. The latter did not particularly care about the preservation of ancient Bulgarian and Serbian Christian holy sites. Churches and monasteries fell into desolation and were destroyed.

First of all, the collaboration concerned the preservation of national sacred sites. In the XV century, almost all the Orthodox nations had fallen into political dependence from Turkey. The latter did not particularly care about the preservation of ancient Bulgarian and Serbian Christian holy sites. Churches and monasteries fell into desolation and were destroyed.

The Russians came to the rescue. Traveler monks from faraway Muscovy regularly visited Bulgaria and helped in an organized way. They brought silver, utensils, and precious liturgical clothing. There were also builders, icon painters, and teams of craftsmen who restored churches and monasteries that had suffered during the turbulent years of wars. Bulgarians were not allowed to keep their own printing house. So, starting from the end of the XVI century, books came to them from Moscow as well.

When monks from the Rylsky monastery arrived in Moscow, Tsar Ivan IV gave them a charter that allowed them to collect funds from all over Russia. And he himself did not remain indifferent to the troubles this ancient monastery was facing. The Zografski Bulgarian monastery on Mount Athos also received Russian aid.

At the beginning of the XVIII century, when a part of Serbia fell under the rule of Austria, Russia helped the Serbs to establish a Church school in the city of Karlovac at the request of the Metropolitan Moisei Petrovic.

„I do not ask for material amenities, but spiritual ones. I do not demand money, but help in enlightening the souls living amongst us. Be a second Moses to us and deliver us from the Egypt of ignorance!» – the Metropolitan wrote to Peter the Great.

The first Russian teacher, Maxim Suvorov, arrived in the Balkans during the rule of Peter’s widow and successor, Catherine I. His initiative was supported by dozens of other teachers who raised many a generation of the Serbian clergy.

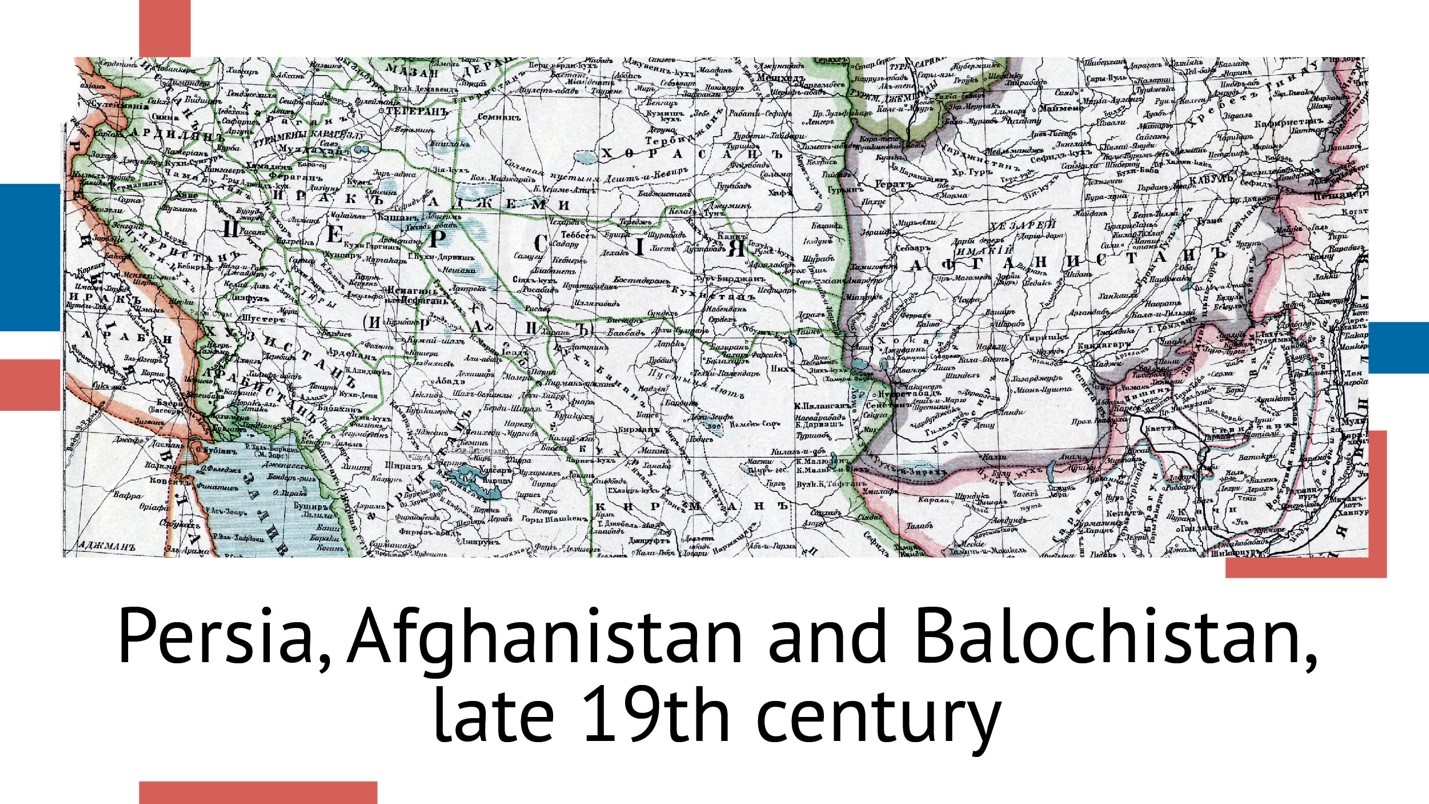

Persian Motives

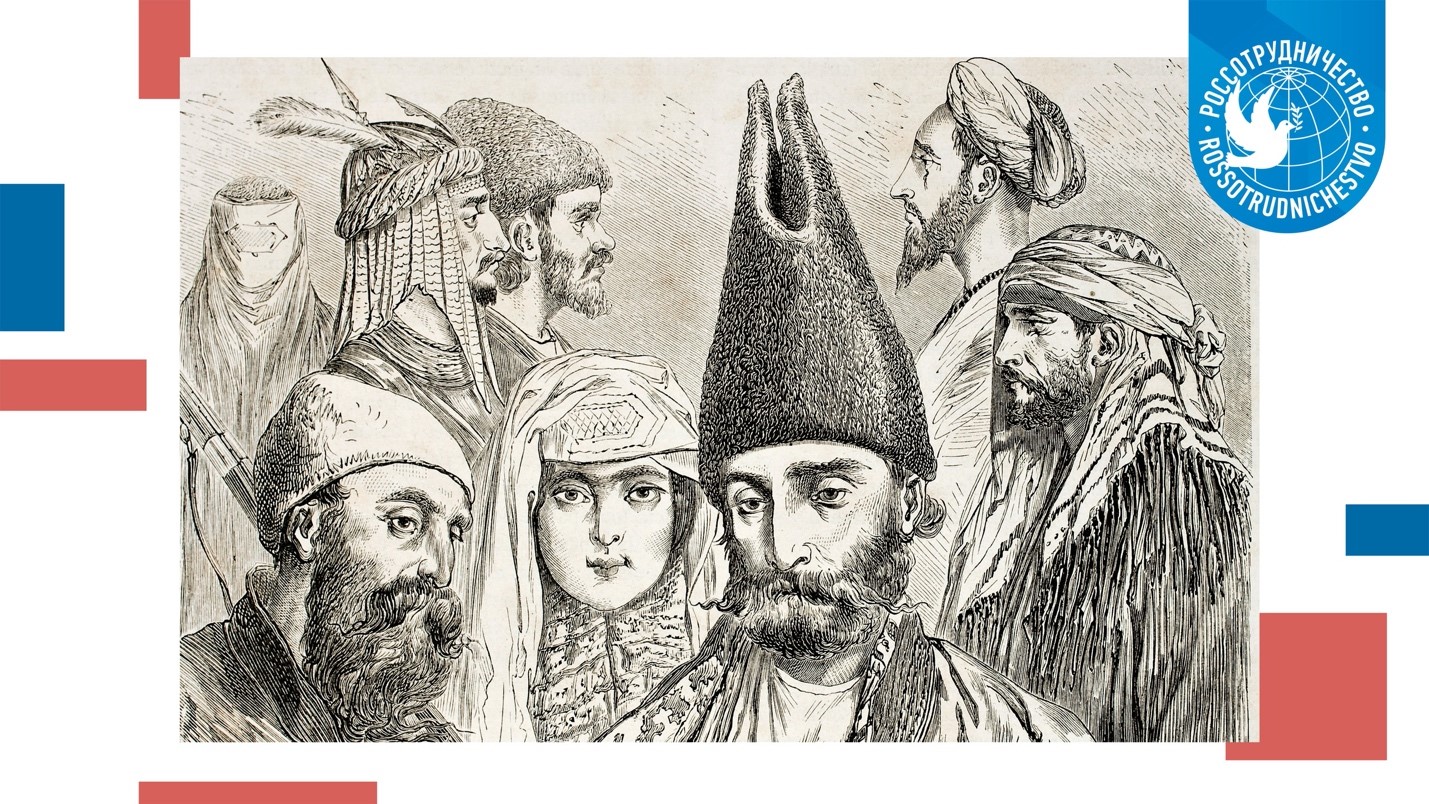

The Persian Empire is the Eastern neighbor of the Russian Empire. Our Nations have fought only once, whereas they have cooperated for centuries. Iran is a great civilization with a long tradition. Envoys from the neighboring snow-covered Empire helped the Persians to learn the secrets of modern technology. At the invitation of the Iranian authorities, Russian technologists helped to build a state-owned textile factory in Tehran in 1857 for example.

The Persian Empire is the Eastern neighbor of the Russian Empire. Our Nations have fought only once, whereas they have cooperated for centuries. Iran is a great civilization with a long tradition. Envoys from the neighboring snow-covered Empire helped the Persians to learn the secrets of modern technology. At the invitation of the Iranian authorities, Russian technologists helped to build a state-owned textile factory in Tehran in 1857 for example.

Until the end of the 1850s, Russian specialists in casting, sugar processing, and writing paper production left for Iran after agreements with Persian diplomats. They not only set up production but also, at the request of local nobles, taught the Persians the wisdom of their professions. Russian craftsmen also built the first windmills in Persia, which delighted the local population. This continued throughout the XIX century.

Naturally, much depended on the preferences of the Persian shahs and influential dignitaries. Many of them were supporters of isolationism, and they were not enthusiastic about the activities of Russian (and European in general) doctors, teachers, builders, and technologists. Thus, the government of Shah Nasir al-Din suspended many joint Russian-Persian industrial programs in the late 1850s.

But in Tehran, there have always been „pro-Russian“ court „parties“ that were aware of the benefits of peaceful cooperation between the two countries and they accepted Russian help with much gratitude. Thanks to the „peaceful intervention“ of Russian specialists, crafts and agriculture developed in Persia. Thus, in the middle of the XIX century, Russian agronomists, sent by the Partnership of the Nikolskaya manufactory of the Morozov brothers, established the culture of cotton in Tabriz.

In Astrakhan, near the Caspian sea, a University was organized for the subjects of the Shah of Persia. Thus began a long (and, fortunately, still existing) tradition of establishing educational institutions in our country intended for Eastern, African, and Northern peoples.

The first military doctors from Russia arrived in Tehran in 1804 at the invitation of the Shah. And they stayed in that country for a long time.

The first military doctors from Russia arrived in Tehran in 1804 at the invitation of the Shah. And they stayed in that country for a long time.

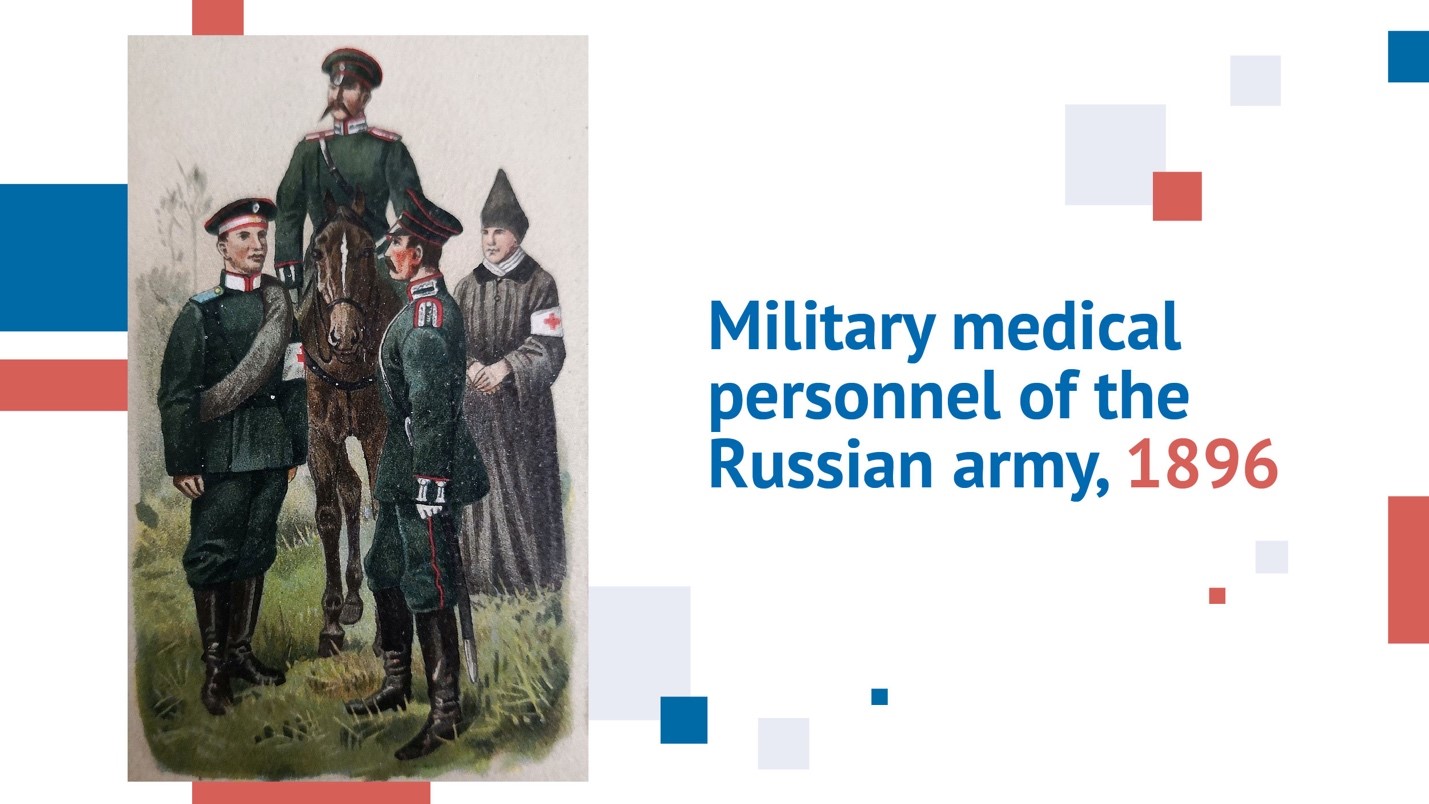

During that time in Russia, there was a centuries-old tradition of military medicine, which saw a particularly powerful development in the XVIII century, when the Germans became our teachers in this field. The Russian doctors served as the first surgeons ever for Persian soldiers.

Russian doctors, passing on their knowledge and skills, opened healthcare stations in Anzali, Astara, Bender-Gyazi и Messagesare. Both injuries and stomach ailments were treated there. Every year, up to 15,000 Iranians received free medical care at these stations. Of all the foreign doctors, the Persians trusted only the Russians.

First, they better knew them: the Russians were the closest European neighbors to the Persians. Second, the Russians, contrary to the British, were very tolerant and respectful of Islamic traditions.

This was also evident during the plague that broke out in the Arab provinces of Persia in 1899. British officials of the sanitary and quarantine services were met with hostility by the residents of Bushehr: they were seen as missionaries who were contemptuous of Islam. Russian doctors were much more diplomatic in this respect, and the Persians gratefully resorted to their help.

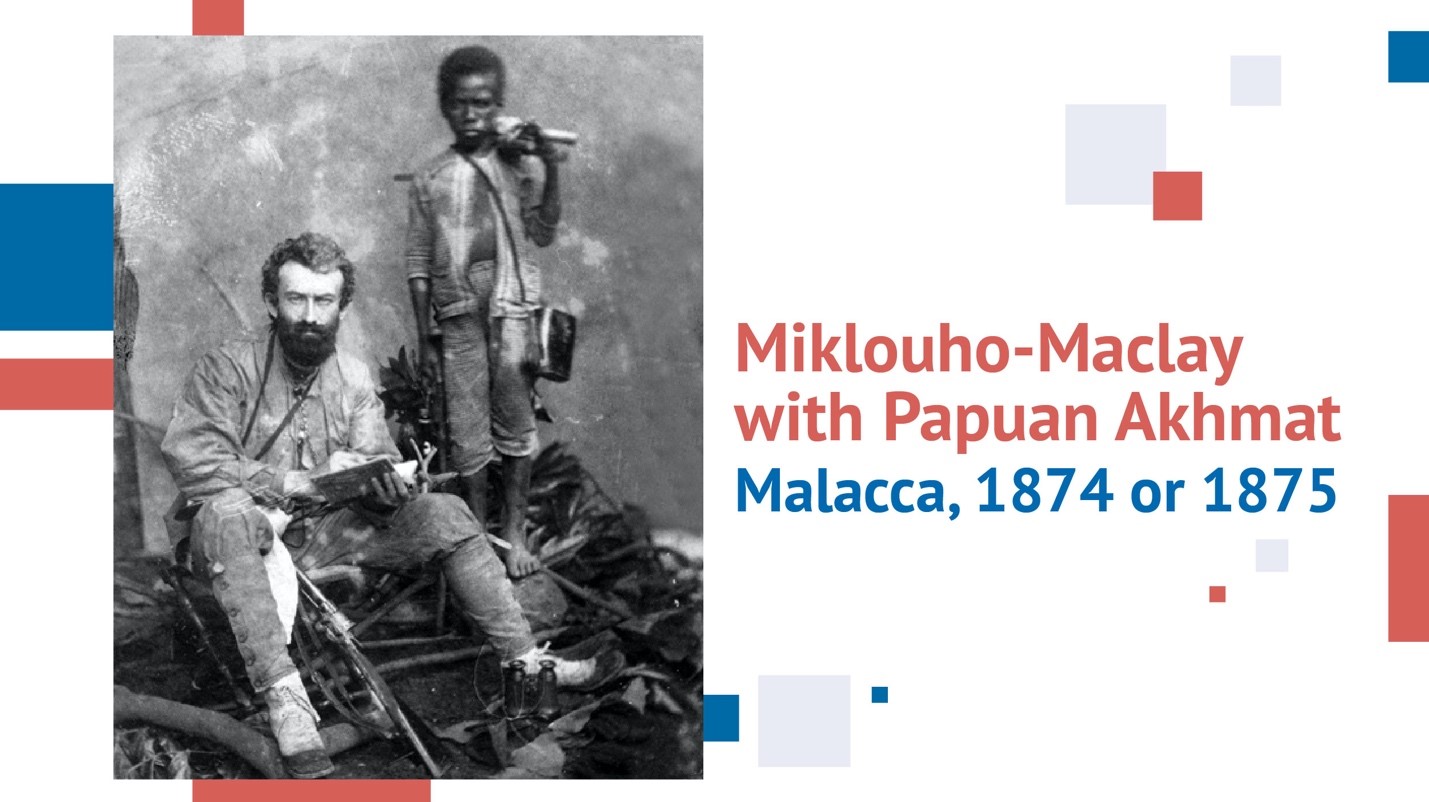

Generally, great Russian travelers were also outstanding enlighteners. Perhaps the most striking example in this sense is Nicholas Miklouho-Maclay. His work became an example of humane and considerate attitude towards the peoples whom he brought Enlightenment. He became the founder of elementary medicine and hygiene in New Guinea, and he also taught the local population, the Papuans, how to grow mangoes, oranges, and lemons. No wonder that the people of Guinea considered him a miraculous „man from the Moon“ and a „good spirit“.

They had a belief, according to which, one day, a white man from the moon would visit them and transform their lives. And Miklouho-Maclay brought them axes and shovels from Russia and taught them how to use these tools. Until now, the Russian word „topor“ for „axe“ is still used in the Papuan lexicon. The traveler also taught them how to salt their food, and was the first to try to treat their diseases. He brought a cow and a chicken to the island, taught the natives how to raise them, and as a result, the Papuans began to learn the basics of animal husbandry. Essentially, the traveler saved them from starvation and extinction. They still call cows „bik Maclay“, that is Maclay’s bull, in memory of the Russian explorer.

They had a belief, according to which, one day, a white man from the moon would visit them and transform their lives. And Miklouho-Maclay brought them axes and shovels from Russia and taught them how to use these tools. Until now, the Russian word „topor“ for „axe“ is still used in the Papuan lexicon. The traveler also taught them how to salt their food, and was the first to try to treat their diseases. He brought a cow and a chicken to the island, taught the natives how to raise them, and as a result, the Papuans began to learn the basics of animal husbandry. Essentially, the traveler saved them from starvation and extinction. They still call cows „bik Maclay“, that is Maclay’s bull, in memory of the Russian explorer.

The Papuans have yet another legend about the Man from the Moon. One day the tribe, in which he lived, began to prepare for war with a neighboring tribe. „What are you going to fight for?„, he asked them. It turned out that there was no special reason for the war, and that it was „just tradition“. Then the Russian traveler said sternly: „No wars! Otherwise I will set the sea on fire!„. First, the natives were skeptical of this threat. But Miklouho-Maclay asked them to bring some sea water. He added some kerosene to the bowl and set it on fire. The water was in flammes! Startled, the Papuans realized that it was better not to argue with this man. And the constant senseless wars between the tribes stopped.

For the future happiness of Humankind…

The construction of the Chinese Eastern Railway brought Russia closer to the peoples of the middle Kingdom. More than once, our doctors have helped our Eastern neighbors in the most perilous situations. The activity of the Russian medical team during the Manchurian plague epidemic of 1910-1911 was a real medical exploit. They were volunteers or, as they used to say in Russia those days, „hunters“. Following the call of the famous bacteriologist Danylo Zabolotny (1866-1929) and, of course, at the invitation of the local authorities, they went to Manchuria.

The construction of the Chinese Eastern Railway brought Russia closer to the peoples of the middle Kingdom. More than once, our doctors have helped our Eastern neighbors in the most perilous situations. The activity of the Russian medical team during the Manchurian plague epidemic of 1910-1911 was a real medical exploit. They were volunteers or, as they used to say in Russia those days, „hunters“. Following the call of the famous bacteriologist Danylo Zabolotny (1866-1929) and, of course, at the invitation of the local authorities, they went to Manchuria.

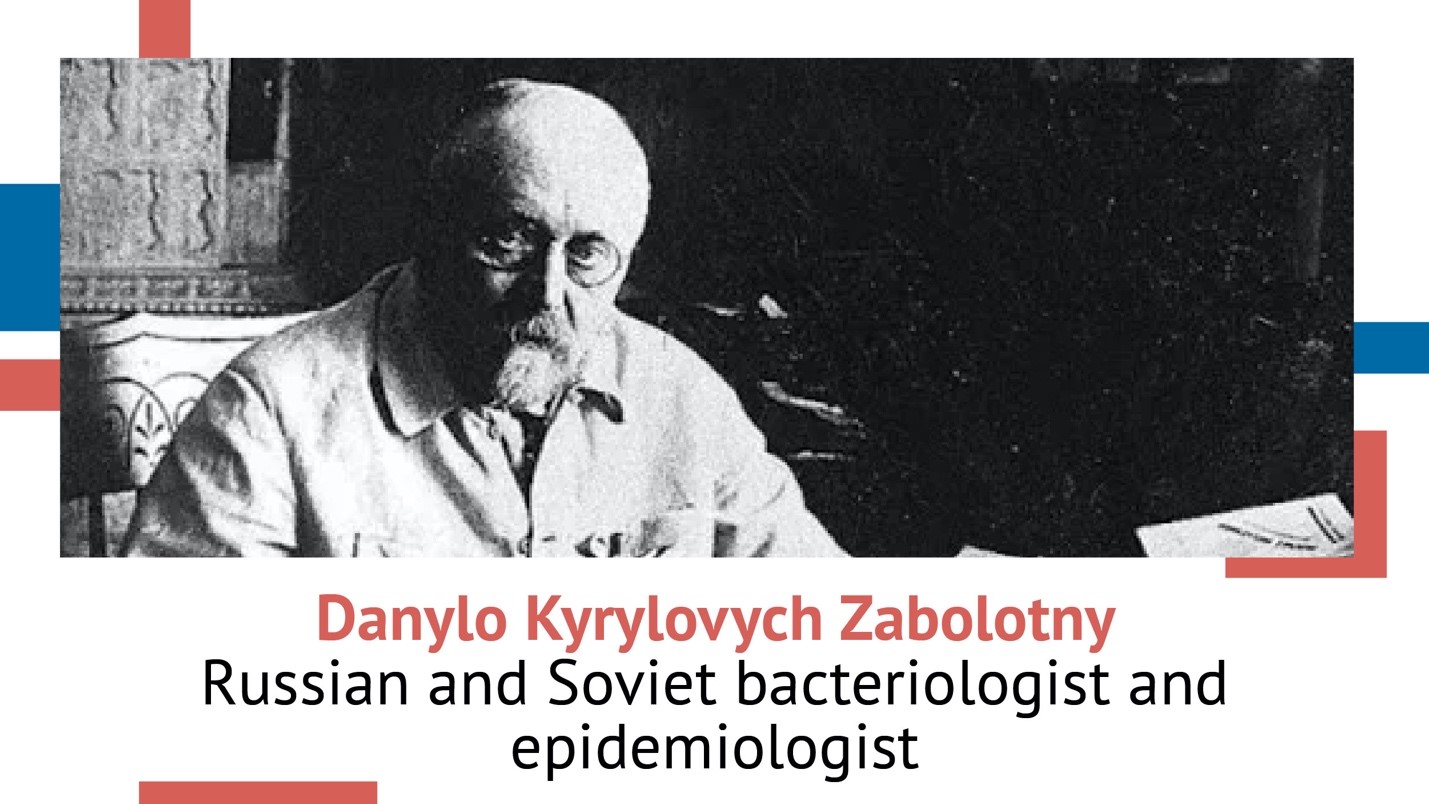

We should tell you a little more about academician Zabolotny. After graduating from the Novorossiysk Imperial University, he worked at the Odessa bacteriological station, studied cholera and various forms of plague. Then, he graduated from the medical faculty of Kiev University as an external student. His life’s work was the fight against epidemics. Zabolotny was the first one to treat children with an anti-diphtheria serum. He participated in expeditions to localize the plague in India, Iran, Mongolia, and Scotland. By 1910, he had gained a unique experience.

We should tell you a little more about academician Zabolotny. After graduating from the Novorossiysk Imperial University, he worked at the Odessa bacteriological station, studied cholera and various forms of plague. Then, he graduated from the medical faculty of Kiev University as an external student. His life’s work was the fight against epidemics. Zabolotny was the first one to treat children with an anti-diphtheria serum. He participated in expeditions to localize the plague in India, Iran, Mongolia, and Scotland. By 1910, he had gained a unique experience.

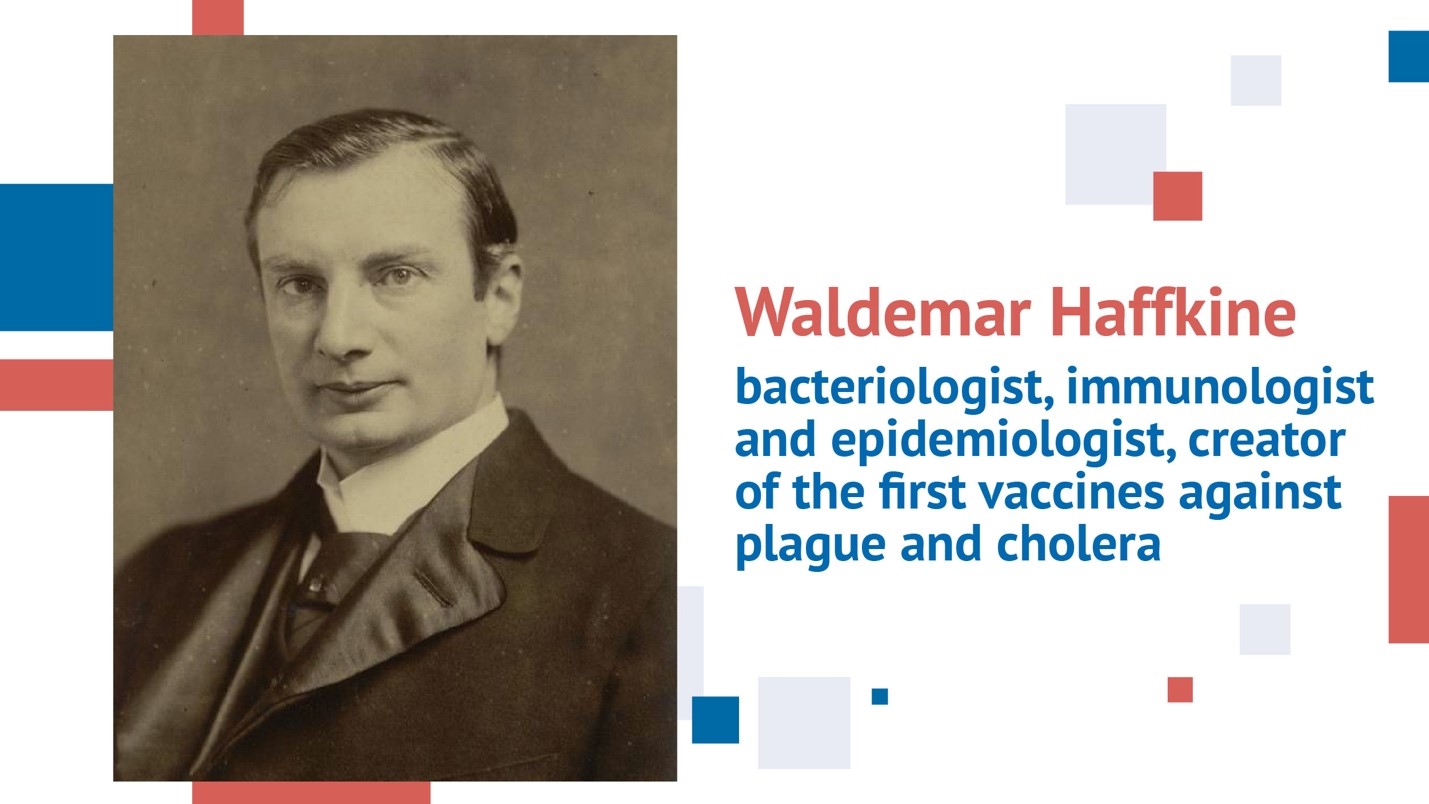

At that time, no one knew how to effectively cure those infected with deadly diseases, and the main task of the detachment was to localize this outbreak of pneumonic plague, which claimed at least 60 thousand lives. First, the Russian envoys had to collect the corpses and burn them, destroying the plague bacteria. Medics vaccinated Chinese people living in the infected area with Vladimir Khavkin’s vaccine, but, unfortunately, it could not cope with this form of plague.

Khavkin invented his vaccine in 1896, and in India alone, more than eight million people living in infected areas owe it their lives. But while the vaccine worked perfectly against the bubonic plague, it was powerless against the pneumonic plague that Russian doctors encountered in Manchuria.

It was a real war against the „black death“. About forty medical workers died, treating local residents, keeping to the end the Hippocratic oath. The Student Ilya Mamontov’s letter, which he sent home before his death, is still remembered in history:

It was a real war against the „black death“. About forty medical workers died, treating local residents, keeping to the end the Hippocratic oath. The Student Ilya Mamontov’s letter, which he sent home before his death, is still remembered in history:

„Dear mother, I’ve fallen sick with some insignificant [disease], but since you don’t get sick [here] with anything but the plague, it must be the plague… The life of one individual is nothing compared to the lives of many, and sacrifices are necessary for the future happiness of mankind.“

He didn’t die in vain. By applying strict quarantine measures in Manchuria, the doctors managed to stop the spread of the plague. In February-March 1911, the disease receded.

Author: Arseny Zamostyanov, Deputy Editor-in-Chief of the magazine “Istorik”